Menswear rules. The almighty force that has the power to tear the menswear community apart, resulting in polarizing views which seemingly would never be reconciled.

Yet, whether you adore the rules dearly or despise them, I am certain that most of us would agree that without knowing and practicing them in the first place, we wouldn't have been able to develop our personal style which we are proud of. Hence, as the general rule of thumb in this area suggests — we should know the rules so that we know what, and what not, to break.

But is there more to this 'truth'? That's where this article comes in. In today's write-up, I will be investigating how menswear rules actually benefit (or impede) the various fields of sustainability.

Of course, it goes without saying that measuring sustainability is no mean feat (see an earlier article 'How sustainable is bespoke tailoring?'), let alone if we were to evaluate more abstract notions like menswear rules. Truth be told, there isn't even a universal answer on what constitutes menswear rules. What this implies is that we could only formulate our definition and then evaluate the principles of action associated with the rules.

Hence, considering this is a topic that could easily be swung to the subjective side, I will, in return, assess the rules based on how well they perform according to some widely-accepted indicators of sustainability.

Anyway, more on that along the way.

Definitions and methodologies

To start off, let's set the scope of the types of menswear rules, as well as the forms of sustainability, which we shall consider.

Menswear rules are plentiful. 1) Some serve a functional purpose, say, to wear fabrics of similar weight or to unbutton your jacket when you sit down. 2) Some exist because of cultural traditions, say, 'No brown in town'. And 3) some are simply concerned with the material or the visual appearance, namely the pattern, texture, and color-matching, the cut of the garment, and so forth.

Here, I will only focus on the latter two categories as they are often more contentious. One could, of course, argue that the pragmatism behind the former rule category is still subjective to one's interpretation. Needless to say, for most, these rules make logical sense to be adhered to.

As for the types of sustainability, apart from the usual environmental and social variants which I emphasize, I will also be looking at cultural sustainability in today's write-up.

Now, you may wonder what is cultural sustainability and why does it matter in our discussion?

In short, cultural sustainability accentuates the maintaining of cultural practices and beliefs. What differs the concept from social sustainability is that the former goes deeper than the quantitative measurement of human well-being — say, whether individuals and communities are adequately paid or not — and touches on topics such as identity and tradition.

Unfortunately, cultural sustainability, as a concept, is often missing from the wider conversations on sustainable development. Two reasons as to why this is the case.

1) Empirical difficulties. First of all, the ideals that are advocated as a part of cultural sustainability are mostly qualitative, meaning they are difficult to be implemented. Then, you have anthropologists and creatives who are rarely involved in the talks regarding sustainability, largely due to how the field was set up initially. Together, these two factors create additional barriers to the materialization of cultural sustainability.

2) Some of us who work and study in this field (myself included) were trained to view sustainability in a hierarchical way. As shown in the figure above, the biosphere serves as the basis for society and the economy to prosper. It is safe to assume that, if we follow this logic, most of us would place cultural sustainability on the 'non-essential' side of the spectrum, light years away from the fundamentals.

While this makes perfect sense in utilitarian terms, whether we should set the bar to this level is a different subject matter. To this, what I would say is that my stance is similar to what Robin Williams' romanticist character, John Keating, from the 1989 film 'Dead Poets Society', would argue.

"Medicine, law, business, engineering, these are all noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life... But poetry, beauty, romance, love - these are what we stay alive for."

— John Keating

Hence, coming back to the question of why is cultural sustainability important, both for all walks of life, as well as this topic specifically.

Truth be told, there is no simple answer for the former. My personal take on this is that cultural sustainability allows us to connect with those who came before and those who will come after us. Sharing beliefs, practices, and values which although may not be universal and eternal, would still create a sense of relatableness amongst us.

Think of it in a #menswear way — if cultural sustainability is unimportant, why on Earth would we Negroni-drinking menswear folk still bother to celebrate in our black-tie attire on New Year's Eve even after a century's time?

Flowing rather smoothly to the latter, cultural sustainability, then, provides us with an additional pair of lens to evaluate classic menswear and its associated practices that other variants of sustainability may fall short to do so.

Anyhow, without striding too far, we shall return to the main conversation for today.

Environmental sustainability

Let's begin with environmental sustainability.

At the first glance, both categories of menswear rules — those that originate from certain traditions, alongside those that are concerned with style and fit — seem to be rather antagonistic towards this branch of sustainability, especially if we take 'resource/ material use' as an indicator. (Also, it makes little sense to use the other indicators as they make even fewer correlations to menswear rules.)

While the aim of the rules varies from one to another, they tend to share a similar end goal — both of them more or less champion maximalism over minimalism. Now, to better understand that, let's examine these rules more closely.

Starting with the cultural traditions group, with rules such as 'No brown in town' or 'Don't wear white after labor day'. Now, there is no denying that both of these traditions exist for a reason. Whether the rule was created to allow a sharp distinction between city and country attire in the case of the former or a contrast between city and summer vacation attire in the latter, they all served a purpose, historically speaking. (We shall further discuss this point later in this article.)

Nevertheless, culturally-significant or not, this sort of rules, by no means, aids the reduction or the minimization of material use to a level that could be sustained. Continuing with one of the aforementioned examples, according to this logic, one would need at least two flannel suits — charcoal for the city and brown for the country, for instance — rather than having one suit that is fitted for every task.

In reality, not only does the rule reduce the versatility of each garment for a rather disputable reason, but it also prompts the wearer to acquire two half-decent suits rather than investing in a well-made, long-lasting though more expensive suit; as everyone has their own budget.

Beyond that, from a demand and supply perspective, one could also suggest that it's a mentality like such — that one needs a different outfit for a different occasion — which contributes to, if not further enables the current fast fashion garment production system and discourages, say, fine craftsmanship.

Likewise, the same critique — that versatility being left out from the consideration of menswear rules — could be used against the style and fit-related menswear rules.

Take the 'Don't wear a pinstripe jacket separately from the matching trousers' rule as an example. The reason why the rule exists is that some (menswear dudes) argue that this pattern is meant to visually elongate the wearer's height. Thus, by breaking the matching pieces from one another, it defeats the purpose of wearing pinstripes.

Sadly, circumstances such as part of the suit becoming an 'orphan' piece (say, due to body weight changes) or the trousers becoming worn out towards the end of their lifetime are not hypothetical scenarios. And in reality, that leaves a sizable amount of clothing unworn after a period of time since they are aesthetically unpleasant to wear separately.

Hence, the question then becomes how far should we uphold aesthetics without sacrificing environmental sustainability, or vice versa. This is a question that frequently pops up in the world of fashion, though less so in the menswear realm. (If you are interested to learn more about this topic, check out the further readings included below.)

Taking a step back, whether the group of rules poses a 'cultural traditions' versus versatility or an 'aesthetics' versus versatility situation, they both reinforce the idea that maximalism is much preferred to minimalism in the world of classic menswear. It presents the case that 'the more garments you have, the less likely you will be breaking such rules'.

But is there more to this one-sided picture?

As you may have noticed, so far we have been considering material use mostly from an individual wearer's perspective. However, as far as quality garments go — and even those that are made bespoke to a customer — many of them are not just worn by a single wearer during their lifetime.

We need not look far, as this is evidenced by the ever-growing amount of e-commerce sites selling second-hand/ vintage clothing. (Drop93 and AU DRÔLE DE ZÈBRE are some examples of brands that I have covered recently.) Furthermore, it is even projected that the Resale market will grow five-fold in the next 4-5 years while traditional retail will shrink by 4% according to Thred Up.

So how do menswear rules come into play and help reinforce this norm?

Many of you may be familiar with the saying that menswear has mostly remained the same for the past 70 years or so. For instance, suits, overshirts, denim, and many more that have been worn for decades are still relevant in today's world. This is not a particularly new nor revolutionary idea.

Yet, the important question that is missing is that 'what is it about classic menswear that allows it to persist, whilst other styles, say streetwear or even certain genres of womenswear, are just a flash in a pan?'

I am keen to believe that this is where the rules concerning style and fit become ever more important, or perhaps even pose as the foundational building block to this argument. Hear me out.

As overlooked as this distinction may usually be, the main emphasis of menswear rules is what sets classic menswear apart from other styles.

Instead of 'what do you wear to look trendy?', the question that menswear rules for decades have prompted us to think about is 'what do you wear to dress well?' From here, the approach as to what to wear deviates from one of 'say, wear garments in the Pantone color of the year or whatever the most hyped celebrity is wearing' to one of 'dress in garments of the right color and proportions that accentuate your body and facial features in the best possible way.'

Now you may wonder, with such a strong emphasis on personalization, aren't menswear rules forbidding the exact thing I am advocating for — which is whether garments could be switched hands or passed on from one generation to another for the purpose of reducing material use?

Here, I think it's crucial to ask ourselves what the outcome would possibly be if we were to dress according to the 'what do you wear to look trendy?' approach, and then compare it with the implication of wearing clothing that accentuates your feature.

For the former, you would most likely end up with a wardrobe of garments which could be considered as 'period wear' in two decades' time. True, you could argue that certain clothing could be repurposed or altered just like what we do in bespoke tailoring, but remember — not all styles could be successfully transformed into something that's wearable. Moreover, it's unlikely that they would be recycled either. According to BBC Future, globally only 12% of the total materials used for clothing result in being recycled.

Meanwhile, for the latter, even if the garments were made bespoke for you, chances are someone else could still fit in your clothes in the future. Don't get me wrong, human genetics are unique — in fact, DNA codes are more varied than the rest of the genome if they are linked to facial features — but I doubt that anyone would argue that in twenty years' time, no one else would have a chiseled jaw like yours to be complemented by a cutaway-collar shirt. Similarly, it's unlikely that no one else would have narrow shoulders to fit in your jacket with extended shoulders.

I am far from an anatomist myself. Nonetheless, I think we could agree that body features and facial details are things that change slower than fashion trends under most circumstances. Next time when you encounter a garment that appears mundane but suits you perfectly, just take good care of it. It could potentially be passed on as an heirloom.

Social sustainability

Moving on, let's examine what is the impact of menswear rules on social sustainability.

Before we begin, it should be stated that despite menswear rules being rules, and rules being a social construction, this does not imply that there are a considerable number of indicators that could be used to evaluate how the rules are promoting or discouraging social sustainability in our case. Consequently, we will quickly go through the criteria that have the strongest correlations with menswear rules. (If you are interested in this subject matter, however, check out this table.)

The obvious indicator(s) to discuss in-depth would be — 'How good are menswear rules in improving (or at least sustaining) the livelihood of those who work in the menswear/ arts & craft industry?' Or 'how well are menswear rules in promoting persons with exceptional skills?' After all, there aren't menswear rules to be spoken of, if the artisans and craftspersons who make our clothing, shoes, and accessories can't afford to work in fields that they are passionate about.

And the answer, in my honest opinion, is one of a yes and no.

On the plus side, these rules keep the trade going. Without the rules to function as a guidance or as a source of knowledge provider, it can be easily assumed that an average person would not know what to look for when acquiring menswear pieces. And thus he or she would be even less likely to turn to a specific atelier or craftsperson.

For instance, without having an understanding of how the shape of a shirt collar and the size of the tie knot complement one's facial feature differently, one is less likely to look for and acquire pieces from a shirtmaker and tiemaker for their a more sophisticated collection of offerings. Instead, they assume what the majority of the population wears is correct and follow suit. Such behavior, also known as observational learning in the realm of social psychology, is certainly not unheard of in the world of fashion. (See a case study on this topic here.)

On the other hand, there is also some truth as to how menswear rules discourage artisans with exceptional craftsmanship but with unconventional designs and methods; or worse, innovation in general. This especially applies to those who play with colors or silhouettes.

The question then becomes one of whether the promotion of social sustainability under such circumstances conflicts with the long-term environmental sustainability of certain garments, or vice versa. But this relates to a wider discussion which we will save for another time.

Cultural sustainability

Finally, we reach the climax of this write-up with the dynamic between menswear rules and cultural sustainability. After all, this is the variant of sustainability that notably has the most consequential points of overlap with menswear rules.

Now, one point that I am particularly inclined to discuss in this section is that — in order to buy into the art of classic menswear, one also needs to first understand and agree with the function of the rules. Naturally, then, for our indicator of excellence for this final branch of sustainability, it would be one of 'How good are menswear rules in promoting the art of wearing classic menswear alongside its associated lifestyle?'

If you recall from the start of this write-up, we have discussed the idea that there are various genres of menswear rules. Up until now, we have validated the usefulness of the more 'pragmatic' rules and have since accepted the benefit of rules that ensures garments have an enduring appeal. Consequently, we could claim that the rules are mostly on good terms with cultural sustainability.

That being said, we have not entirely wrestled with the cultural traditions genre and its implication on cultural sustainability. As a matter of fact, this is what we will focus on for the rest of this section.

As I pointed out earlier in the environmental sustainability section, the cultural traditions sort of rules is not ungrounded, since it manifests as an inseparable part of a lifestyle that our forefathers used to practice (and some of us still do). The problem, however, lies in the fact that the rules are often misinterpreted and thus poorly implemented in today's world.

Again, taking 'no brown in town' as an example. More than just about the distinction between the navy and grey (and historically black) palette of the city and the earth tones of the country, the intent of this rule is also to reflect the city-by-the-week and country-by-the-weekend kind of lifestyle many practiced back in the day.

Unfortunately, some contemporary practitioners of these rules seem to have failed to realize the intent behind the creation of the rules and take their literal meaning for what it is. Worse, there are certain circumstances where they would force these rules upon others. This is occasionally manifested in the form of office dress codes but is not limited to it.

Regardless, this behavior raises some cultural relevance issues for those who simply want to enjoy classic menswear but do not follow these historical-cultural practices.

The broader question which I suppose we have to ask ourselves is whether by blindly upholding such obsolete rules and binding classic menswear with a certain lifestyle, not only are we snowballing their irrelevance but also are we hindering the overall appeal of what the menswear rules are defending — which is the art of wearing classic menswear? In other words, do we value each and every menswear rule regardless of its context or classic menswear as a whole?

I think the answer is rather clear on which approach is best for maintaining our beloved cultural practice.

Final remarks

Coming back to a full circle to where we have started then, it's tricky to determine whether menswear rules are purely good or bad for sustainability.

Not only is this caused by the wide range of menswear rules (and how ambiguous they are), but also the same rule could have a contrasting impact on different branches of sustainability. Similarly, we have witnessed how conversations such as 'aesthetics vs environmental sustainability' and 'creative freedom vs environmental sustainability' could spark fierce debates that would hardly come to any conclusion.

With that said, there are still a few things that we could take away from this conversation.

First off, rather than taking 'sustainability has no relevance to our thinking towards menswear rules' as an answer, the better approach would be to acknowledge that whichever menswear rule we choose or choose not to follow, it would still have some impact on sustainability; even if the implications aren't all that apparent.

Secondly, apart from taking 'know the rules so that you know what and what not to break' as a motto, we could also consider which rules are necessary or unnecessary to follow for the sake of encouraging sustainability. After all, menswear is all about owning your look.

Lastly, as you could see, it is not always possible to satisfy all forms of sustainability at the same time. That being said, instead of seeing the three branches being contentious with one another, the way to go would be to strike your own balance amongst them.

One final word. There are certain limitations to this write-up. The fact that we are discussing three variants of sustainability at a time means that there will be over-generalization here and there. Additionally, we only went through the most pertinent indicator in each section, meaning our understanding of this subject matter might have been quite different if we were to go more in-depth on each topic.

This is a conversation which I may come back to in the future. Hopefully, by then there will be more available data to enhance the quality of our discussion.

Anyway, take care and bye for now.

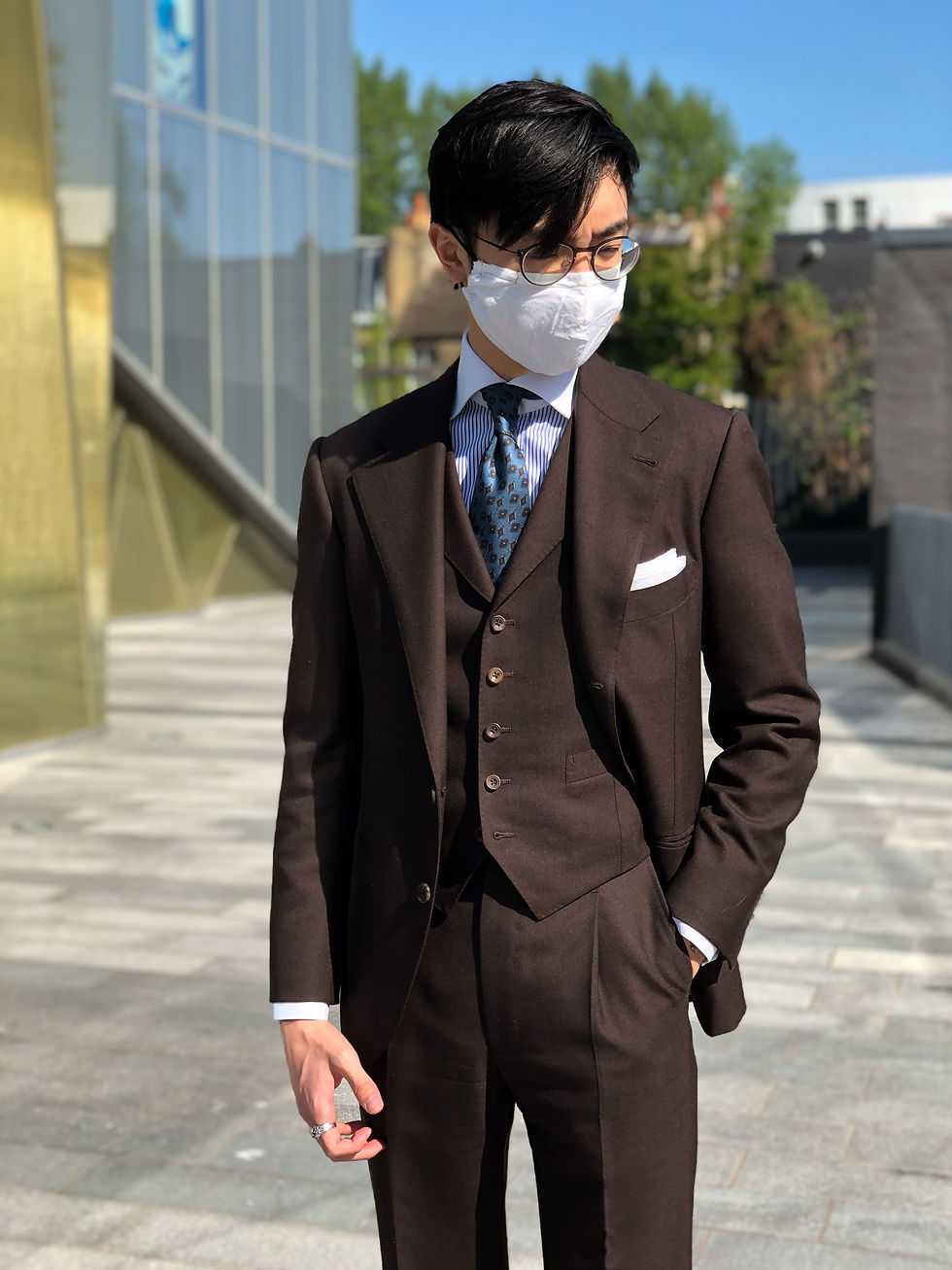

Photography: as stated, otherwise own

Further readings:

-For a literature review on cultural sustainability, see the first paragraph of the introduction of Myllyviita et al, 2014

-For more in-depth analysis on the topic of aesthetics and sustainability, see Allen, 2018

-For Thred Up's Full 2020 Resale report, see here

-For a more in-depth analysis of social and cultural sustainability indicators, see this table from Axelsson et al, 2013

-For a list of social sustainability indicators, see p.8 of this working paper by Colantonio, 2007

-For a case study on how observational learning influence fashion, see this case study by Ranathunga, 2014

Comments