I know, I know. I did hint to some of you that this article would have been published by last August. Alas, God has a different plan for us and this jacket — which I will explain further as we go along — and hence, the write-up had been left on the shelf until now.

Worry not, however, as I can assure you that what I have gathered from studying the Kent 4*1 DB style over the past six months will undoubtedly enrich today's conversation. For starters, let's say it has allowed me to have a better glimpse of the sheer complexity to get this jacket right from a mechanical perspective.

So sit back and buckle up as we transverse through the numerous aspects surrounding this sartorial fantastic beast and its making. Enjoy.

Inspiration and the Kent 4*1 DB Style

Like many sartorial folktales that came before, this project started with two menswear enthusiasts fantasizing over jacket cuts from the (not-so?) distant past, contemplating how certain aesthetics have ceased to exist despite exhibiting a dearing appeal.

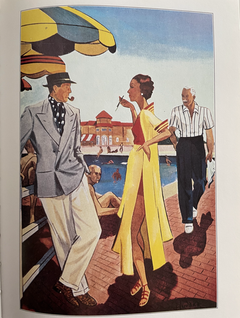

In this case, the Kent 4*1 DB style is one that we consider to be overlooked. Instantly distinguishable from the silhouette of a contemporary double-breasted jacket which places terrific emphasis on the sharpness of the peak lapels and the wearer's heroic figure, the Kent style — with its extra-elongated chest, outer pockets-aligning low-buttoning point, and roomier fit — offers an alternative interpretation with its slouchy and relaxed look.

Indeed, it is unsurprising as to why this style was well-favored by the better-known brother of the Duke of Kent, the Duke of Windsor, and had a recurring appearance in countless golden age Apparel Arts illustrations.

Now, even though it is never an easy task to predict where menswear will be heading towards — which is why I often champion the notion that we should dress according to our personal preference — it is, perhaps, not an overstatement to assume tailoring will be more comfort-oriented in the post-pandemic world.

Thus, the Kent style and my ever-growing tenet that tailoring should be about comfort above all else, swiftly resonated with one another, leading to the dawn of this project.

The process

Nevertheless, like many great ideas, the implementation part is always the most challenging step.

With the number of 6*2 double-breasted jackets getting commissioned declining with each day's passing, so too are there even fewer tailors that have a distinctive house style for 4*1 DB jackets. Truth be told, the artisans that I could name directly off the top of my head are Musella Dembech, A Caraceni, and WW Chan, etc — all based outside the UK.

Hence, given how limited my options are, alongside the fact that I couldn't visit these artisans while the world has been in lockdown, I returned to Whitcomb & Shaftesbury, where I had some of the more intricated designs — the camel polo coat, for instance — turned into reality rather successfully.

It was, therefore, with all these past commissions taken into consideration that I decided to take a leap of faith and have the jacket made by Whitcomb, despite being aware of the fact that the Kent is not the style the bespoke tailor is known for.

As it turned out, the process to get this DB to its current shape had not been the most straightforward one.

Showcased above is a photo taken at the first-fitting stage. Upon close examination, you could easily spot that despite featuring a lower-than-usual buttoning point, the jacket still retained a rather sharp English aesthetic.

From the moderate amount of drape around the chest and the nibbed waist to the straight lapels and small hips, these elements would certainly have been flattering if the jacket was to come in a 6*2 configuration.

Needless to say, in order to remain faithful to the Kent style and achieve a more relaxed appearance, some major adjustments were necessary.

First off, the shoulders have been extended to allow more drape around the chest.

While letting out cloth around the chest would normally suffice in providing more comfort, what was attempted here was to create a shape that mildly resembles the voluminous 'V-shape' drape that was extremely popular in the 30s.

On top of that, the jacket is made out of a fabric that contains ~40% silk, which is notoriously known as not holding any shape (more on that later). This proves the broadening shoulders-approach to be the better alternative.

What follows was the reexamination of the gorge height.

Now, gorge height is one of those elements that really depends on personal preference. Some tailors I have worked with like to place it lower since it won't 'sit right in front of your face.' Others favor the gorge to be as close to the shoulders as possible since the further-elongated lapels could create an optical illustration that the wearer has a longer upper body.

In this case, Whitcomb's house style usually errs towards the latter, as evidenced in the various SB jackets they have made for me previously. What is crucial to bear in mind here, is that considering the jacket is rolling at a much lower point than the natural waist, the elongated lapels effect could still be achieved even if the gorge is placed a tad lower.

Thus, as you can see in the picture above, Suresh and I decided to settle on the gorge height on the right side (from our angle). We might have gone even lower than that for the final product.

Speaking of the low-buttoning point, this is the detail that has proven to be the most contentious feature.

Normally, on a 6*2 jacket, the double piping pockets will be placed in between the middle and bottom row buttons. Hence, naturally, if you convert the jacket into a 4*1 piece, the pockets shouldn't be affected, right? Not that simple.

If you look closely at the collage above, you can see that under the Kent style, the pockets are usually aligned with the bottom row buttons. In my view, the latter's configuration offers a much neater appearance as the number of horizontal 'lines' around the bottom half of the jacket would be reduced, or at least more spaced out from one another.

Needless to say, this is what I went for ultimately.

That being said, it was the events that followed the first fitting that didn't work so well.

Shortly after the first fitting, and around the same time the jacket is at Whitcomb's India workshop, India went into (a month-long?) lockdown. As a result of the lockdown situations (with the UK and India coming one after the other), we rushed the commission and skipped over the second-fitting and go straight to the final version of the jacket.

Frankly speaking, this is one of those scenarios that illustrates how important being patient is.

Upon collecting the DB, one recurring feedback that I kept on receiving is that the bottom row buttons are not level. You can spot that in the picture above, with the buttoning point being pulled in all directions and dragged slightly higher than the button next to it. Consequently, the skirts of the two sides are of different height as well.

Why is that happening, you may ask? Let's take a step back and examine the various parts of the jackets that induce the pull.

The most apparent answer is that there wasn't enough fabric in the front. If you compare the jacket with all the other Kent-style DBs featured earlier in the collage, you could sense that the issue doesn't originate from the placement of the bottom row buttons — the buttons are placed exactly where they need to be. This could only mean the overlapping side of the front panels is not wide enough. Indeed, this can happen when you attempt to convert a 6*2 into a 4*1 since this is not a normal anchor point.

This leaves us with two solutions — move both of the bottom row buttons towards the center, or let out more fabric from the side seams. (Don't forget, there will always be less flexibility once the buttonholes are placed!)

While the former seems to be the simpler, 5 minutes quick-fix solution, it could cause stylistic dismay instead. Under this scenario, the buttons would be too close to one another, thus causing an optical illusion that I have very narrow hips. Consequently, the solution can only be option 2.

While this addresses the 'pull' issue, the 'drag' part remains unresolved.

When I brought the jacket back to Whitcomb last fall, Sian (the cutter) suggested that it may have to do with the fact that the shoulders are not balanced, with the right side of my shoulders being more slanted.

Now, technically this issue should have been taken into consideration prior to the commission as Whitcomb already has my paper pattern. Why this problem flew under our radar, therefore, would be because of the more recent developments to my posture.

Truth be told, this could occur to any of us. Your shoulders could become less slanted overtime. Or sometimes, you just lift the more slanted side of your shoulder unconsciously; thus pulling up the entire front panel of that side of the jacket without even realizing it. In this case, there is a little bit of both that is at play here.

For that reason, despite having Sian pick up the shoulder on the other side, the 'drag' issue still occurs depending on my posture at a particular moment. Say, in the photo above, not only is one side of the button sitting higher than the other but so is the Tautz lapel on that side, as shown in the picture above. Meanwhile, there are also circumstances where the two front panels are completely level, as showcased in the picture below.

My word of advice, therefore, is just don't think about it. If you are wearing a 4*1, chances are you are too much of a fabulous unicorn where others wouldn't even pay attention to the drag. Or as they say, embrace the imperfections since it is handwork.

The fabric

What has been largely missing from our discussion up to this point is the lack of focus on the fabric; and as they say, you can't truly analyze a garment without studying the cloth.

As stunning as it is, this Holland & Sherry fabric (3020107) (in fact one that I kept coming back to in the months prior to the commission) — made out of silk, linen, and worsted wool — is perhaps somewhat responsible for causing some of the aforementioned issues as well.

Given its fabric composition (silk and linen are both very hard fibers!), it may very well explain why the cloth is less gentle and resistant to pulls, especially if we compare it to, say, high-twist wool or cashmere.

On top of that, this also sheds light on why it is more challenging to add shape around the chest. Similar to how a silk tie bounces back in shape after you leave it on a hanger, the silk in this fabric bounces back in shape regardless of your previous pressing efforts. This is why this DB may look boxy at times, with the waist suppression being less visually apparent.

With that said, I should highlight this is, after all, still a beautiful cloth. The melange of colors on this cloth is unquestionably one that is hardly rivaled. Frankly speaking, the cloth could, perhaps, have performed better in a routinary SB jacket commission — one that emphasizes less on the form and shape of the garment — rather than in experiments like such.

I am certain you would agree with my statement upon taking a closer look at the fabric via the picture below.

Going forward

This brings us to the question of what is the moral of this story?

First and foremost, I think this commission validates a point I've raised at the start of the write-up — it is tremendously difficult to get a Kent-style 4*1 DB fitted to perfection in one go, especially if the fitting process is rushed.

Making a Kent-style DB is not as straightforward as making a high-rolling 4*1 jacket, where you would simply remove the bottom row buttons of a 6*2 DB. It requires a certain degree of familiarity with the physique of the wearer and how the changes in the anchor point would affect the gravity of the jacket.

In this case, then, it is not an overstatement that the wearer should take a leap of faith and be more patient with the chosen tailor. After all, if you were to invest in a tailor to make a garment outside of their scope of training, keeping your hopes sky high and expecting perfection for the first commission is perhaps not a brilliant idea.

It is only through multiple commissions where your tailor becomes more familiar with your aesthetic then you can finally say — 'well, I guess my investment has finally paid off!' Jokes aside, really, be patient with your tailor — sometimes they do need that.

Coming back to the jacket itself, there are changes that I would make if I were to commission another Kent-style DB in the future.

Firstly, instead of going for a Tautz lapel, I am more likely to go for a more angular peak lapel. Whilst the story behind the Tautz lapel is always one that keeps me intrigued, the placement of the Tautz in a jacket with rather broad and square shoulders is arguably less suitable. In contrast, a peak lapel, even just by a fraction more angular (15 degrees, perhaps?), could better recreate the aesthetic featured in the sample jackets.

On a similar note, rather than keeping such straight lapels, I am keener on experimenting with a bit more belly at the bottom half of the lapels. It would give off an effect that the lapels are wide up top, but looking considerably slimmer as the eye moves towards the anchoring point. For your reference, it would be identical to the ones featured in picture 5 of the collage above.

Secondly, I would opt for a curvier collar instead of a straight collar. The latter is something we took the design directly from one of the illustrations, though unfortunately, it turned out less astonishing than I expected.

Finally, and echoing what has been briefly mentioned in the last session, I would experiment with a softer yet heavier cloth instead. Like what tailoring technique guidebooks always teach up-and-coming apprentices, always start with a 12-13oz cloth when trying out something new. Alas, we all live and learn.

That's it from me today. Take care and bye for now.

Photography: as credited; pictures featured in the collage are either from "Men in Style" or Pinterest; all else by The Suitstainable Man team

Comments